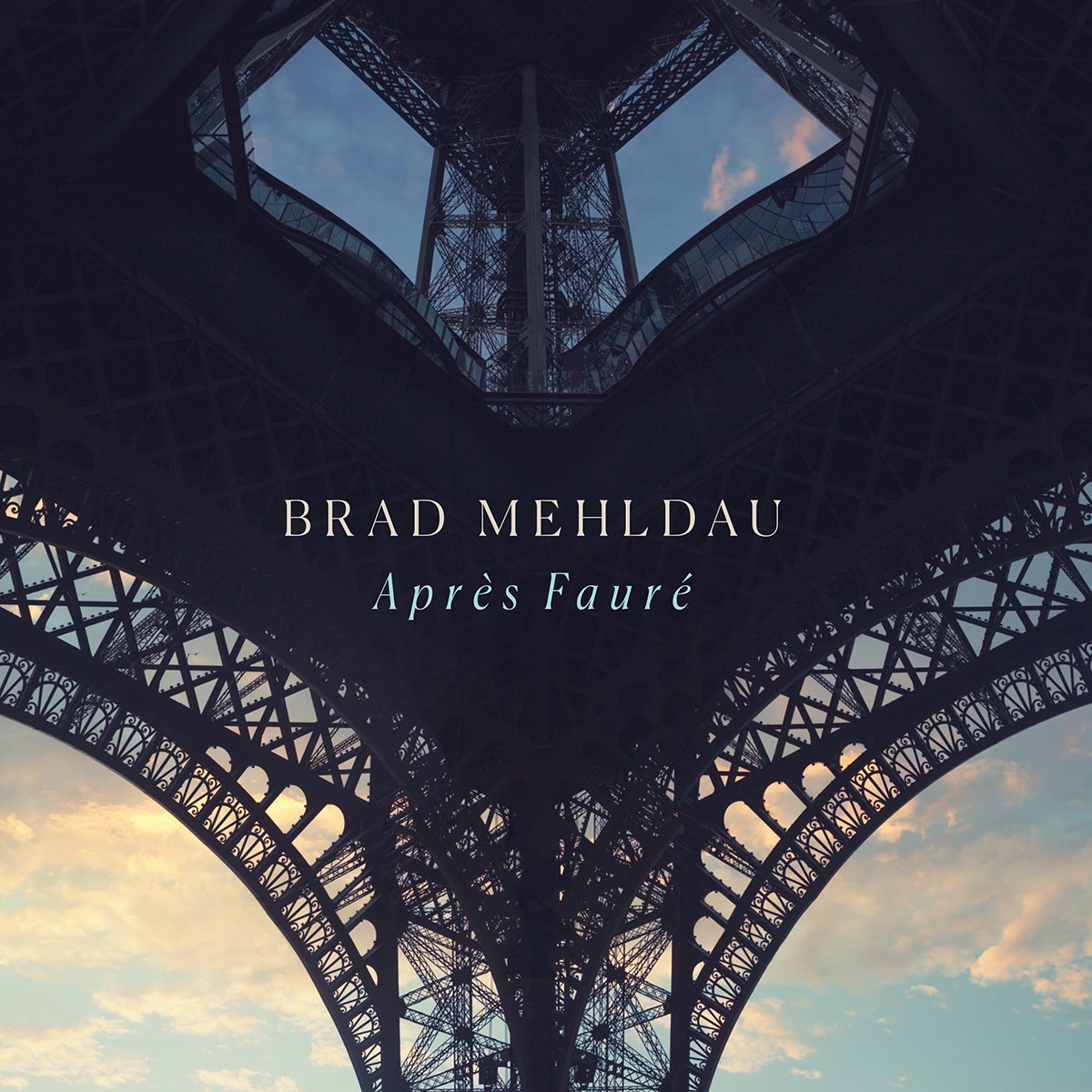

Après Fauré

On Après Fauré, Brad Mehldau performs four nocturnes, from a thirty-seven-year span of Gabriel Fauré’s career, as well as a reduction of an excerpt from the Adagio movement of his Piano Quartet in G Minor, along with four of Mehldau’s compositions that Fauré inspired presented in a group, bookended by two sections featuring the French composer’s works.

Après Fauré

Gabriel Fauré:

1. Nocturne No. 13 in B Minor, Op. 119 (1921)

2. Nocturne No. 4 in E Major, Op. 36 (c. 1884)

3. Nocturne No. 12 in E Minor, Op. 107 (1915)

Brad Mehldau:

4. Prelude

5. Caprice

6. Nocturne

7. Vision

Gabriel Fauré:

8. Nocturne No. 7 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 74 (1898)

9. Extract from Piano Quartet No. 2, Opus 45 (c. 1887): III. Adagio non troppo

Brad Discusses and Performs from Après Fauré

Liner Notes

Fauré, the Quiet Revolutionary

A composer’s late output can be a testament to their unceasing creativity in the face of physical decline and impending demise. If not an outright victory over mortality, it offers consolation, in a kinship that passes through the boundary of time and death. The listener and the great ghost silently communicate: “You are there; I am here, yet we are linked.” There is a quiet poetic justice.

The link, of course, is the enduring transcendence of the music itself. On the one hand, it may breathe life-affirming beauty; or, it may transmit the Sublime: a counterweight to beauty which affirms our transience. In such music and art, we sense a large and fathomless eternal presence, one which may terrify us in its in annihilatory capability, or at least shake us from easy beliefs. If, upon this apprehension, we search back for the consolation of beauty, it is still there, but tempered by awe. Beauty affirms life, but beauty is temporary, because we are temporary. Death lies within it already. Depending on our metaphysical leanings, we may or may not call that “just”, but one thing is sure: this admix of beauty and death is strongly poetic.

In the negotiation between beauty and sublimity, certain late works may tilt to the latter, in what seems like a renunciation. If we know the composer’s earlier output already, and love it with our hearts, we may feel perplexed, or even betrayed – where is that great sunny ghost who consoled me? What we have instead is music that breathes austerity and weirdness all at once. The most familiar model for that uneasy phenomenon is Beethoven, in music like his last String Quartets. Fauré’s late music shares this quality.

I opted to present the four Nocturnes here in a counterintuitive fashion, confronting the listener with the radical tonal language Fauré arrived at near the end of his life in his final essay in the form, No. 13 in B Minor. In this way, one may hear his earlier music in a different light. The Nocturne No. 4 which follows, the earliest of the four, is a case in point. For all its welcoming solace, its middle minor-keyed section foreshadows the sparse, at times desolate atmosphere of the later work.

Gabriel Fauré, who was born in 1845 and died in 1924, composed 13 Nocturnes over a span of 36 years, the first in 1875 and the last in 1921. One can hear that he already displays his own voice in No. 4, but we feel Chopin’s presence, perhaps recalling the famous Nocturne Opus 9, No. 2 in the same key of E-flat. Fauré moved away from the great predecessor, but in a different manner than some of his contemporaries who also wrote piano music that extended from Chopin’s language. Namely, we never hear a system with Fauré. The writer Italo Calvino posited “a method subtle and flexible enough to be the same thing as an absence of any method whatsoever.” Fauré attained that in his final two Nocturnes included here. They are one-offs, completely unique and unrepeatable.

In considering his music on the centennial year of his death, this invites the question: What is Fauré’s legacy? It’s a subject I’ve taken up more than once with other musicians who are passionate about his music, and we have remarked with some puzzlement that Fauré sometimes seems to be a “musician’s composer.” He is not as familiar a name as his younger peers, Debussy and Ravel. There are indeed a handful of well-known classics, like the beloved Requiem, the Pavane, and songs like “Après un rêve” and “Clair de lune”. Yet in my observation attending concerts for a few decades, his piano music does not appear on programs with regularity. Part of the reason may be that his piano output is not overtly virtuosic, and is free of novel pianistic effects.

Another reason may be that Fauré has been what is sometimes called “historically unlucky.” Although they both rejected the designation in reference to their music, Debussy and Ravel are regarded as exemplars of French Impressionism in their field, which presents itself now as a singular entity – a moment in which music and visual art aligned in a particular cultural locus. Posterity favors the umbrella of such a clear historical narrative, one which presents us with a clean break from the past – a rupture, followed by a revolutionary new language which changed everything thereafter. We know that the actual unfolding of creative history never operates like this, that it’s more like series of perpetually overlapping streams.

Yet we may be seduced by the bite-sized edification of such an account, and it makes good program notes. In this case, it invokes a quality we call “modernism.” We associate that quality with Debussy and Ravel, and we do not as readily with Fauré. We must be careful to not romanticize our notions of modernism, for in doing so we risk missing what is modern – that is, perpetually modern, modern still to our ears today, if we pay attention. There is much to find, in this regard, in Fauré’s music.

Fauré has been viewed as a bridge figure, with one foot straddled in the German Romanticism of Schumann and Brahms. How much this is true cannot be fixed with certainty. It is a dangerous game in general to assert influence from one great figure to another, to the extent that it is presumptuous. The phenomenon of influence is a mysterious process, one which continues after the initial encounter, not a fixed moment, and often as mysterious to the artist as it is to their public. Often, a listener’s presumption is a misplaced assessment: it is more about the connections they make between composers and musicians that they love, in their own personal canon.

Nevertheless, it is easy to hear a harmonic kinship, if one may call it that, particularly between Brahms and Fauré. As an example, consider Brahms’ second String Sextet (1865) and Fauré’s second Piano Quartet (1886). In both works, the mediant tonal relationship between G, B, and E-flat is fundamental, and constitutes an organizing formal principle of the multi-movement work. Because they are the same three pitches, I like to think that Fauré encountered the Brahms, an earlier work by roughly thirty years, and it had an impact on him, although of course this is my own connection as a listener.

Brahms builds mystery and poignant emotional admixes from these three tonalities in his first movement, but they are still separate entities. Fauré welds them together in an unprecedented way. Here is a pivotal juncture in the first movement (with the piano arpeggiation reduced to chords). The strings play the melody in unison octaves:

This is a bridge moment, if there was one, and it is also what we could point to as a facet of Fauré’s “sound” – the closest he ever gets to a system in the sense of a harmonic device he exploits with mastery in other works as well. The tonal center is neither G, E-flat or B major, yet is all of them. In the circular logic of the common mediant tones, one could start this phrase at any point and the listener will have the same kind of experience, which is a feeling of vertigo and resolution all at once. On the one hand, the music follows feels romantic in the best sense – at turns dreamy and tempestuous, the way Brahms’ three Piano Quartets can be. Yet those three pitches, G, E-flat and B, form one of two augmented triads that make up the whole tone scale: a row of notes that becomes indispensable for French composers who follow Fauré. Debussy will build whole pieces around it; Messiaen will name it the “first mode” in his book on composition and theory.

Fauré’s uniqueness was to arrive at his proto-whole-tone approach in the context of a well-established existing tonal tradition. Those mediant relationships still play out in the tension and resolution of chromatic voice-leading, and are framed within a Sonata-Allegro form movement, with its larger story of tension and resolution, of dissonance resolving in consonance. That is quite different than beginning a piece in the whole tone scale and “hanging out” in that mode, as a jazz musician might put it, which is what Debussy does so evocatively in a piece like the Prelude, “Voiles.”:

In one view, we can understand this as a 20th Century kind of moment – the earlier composer, still straddling the previous one, has reached a breaking point, and the latter one begins from that point. (Again, I will not speculate on influence, but Debussy’s Preludes were composed in 1910.) We must specify that break though. It is not that Fauré reaches a point of chromatic no-return, and Debussy breaks from functional harmony completely, the way we have (reductively) come to view the relationship between Wagner, Mahler and Strauss the elders; and Schoenberg who follows them. Debussy remains a harmonist of the highest order, but his innovation here is to allow himself stasis, precisely at that break point, in such a way that the whole tone scale is no longer jarring and destabilizing. It has become the home tonality.

Yet when you choose one approach, you relinquish another, and what we relinquish in this approach is the grand narrative of tonality that began to fracture at the end of the 19th century – of tension and resolution through harmonic movement, versus stasis. In the 20th Century, the break from that narrative constituted modernism. One might ask rhetorically, which, if either, is more “modern” for our 21st Century ears – the movement, or the stasis?

This question may have no answer, yet as we move on to consider Fauré’s later oeuvre, it might help us find another way to understand his particular innovation. If we want another word than “modern”, with all its baggage of historicism, we might call it freedom, understood in that way that Calvino imagined – freedom from strict adherence to the rules of tonality, but, just as much, freedom from an obligation to suspend or renounce a tonality which fashions a wordless narrative through its flux of tension and resolution. Such a renunciation become orthodoxy in the 20th century.

As an example of that freedom, consider Fauré’s 12th Nocturne, included here, written in 1915, almost three decades after the Piano Quartet mentioned above. In one regard, we may also call Fauré historically lucky, in that he lived a long life. He began as Debussy, Ravel and Satie’s predecessor, but at this point is their contemporary. Now, he uses the whole tone scale in a bald, direct way, allowing us to bask in its destabilizing sonority for its own sake:

This passage arrives as a maelstrom of heightened tension in the Nocturne, but Fauré is flirting with Debussy’s kind of stasis – in the right hand, the whole-tone scale starts to feel like home base for a moment. The left hand, meanwhile, is close in shape to the melody of Thelonious Monk’s Epistrophy,” and for this listener, taken alone, has a blues character. Fauré bit me so strongly when I first discovered him because of the maximalist freedom on display here. He extends a Romantic piano tradition from Chopin, Schumann, Liszt and Brahms, and at the same time announces an unmistakably French kind of modernism – one that anticipates jazz harmony. There is so much in this one piece.

The 13th Nocturne is a genre in itself. Its opening page presents us with a harmonic landscape that has no corollary, even in his own work. Here is one particularly arresting passage:

With its mix of crunchy chromaticism and not-quite-parallel ascending triads, this music reminds us of nothing else – not even, indeed, Fauré’s own earlier output. More strikingly, though, it has led nowhere else, in an immediately discernible sense. Far from being a pejorative statement, this quality embodies the quiet revolution that Fauré achieved. No composer after him wrote piano music which sounds like this, in the way, for example, that Chopin echoes in Scriabin, Rachmaninov, and Fauré himself. If a composer’s greatness is commonly measured in how apparent their influence is, here the opposite is true: the music is too singular, and remains unassimilable, affirming its genius.

Brahms’s Intermezzo from his last set of four Klavierstücke (in the same key of B Minor, and fittingly, with the same Opus number of 119) shares that closed/eternally open quality. In both cases, the isolation is reinforced by the austerity of the musical texture, which eschews a normative Romantic piano model of songlike melody hovering distinctly over accompanying figuration. Melody and harmony are closely fused, more akin to a Bachian model. There is a new focus in the economy of material, and with that, a certain stateliness, which for the player, must not collapse into rigidity. Fauré’s opening section holds strictly to a four-part texture, and unfolds with a chorale-like solemnity, even as it lands baldly on a C Minor seventh chord on the last bar above, sounding like modal jazz for a wisp of a moment.

Here is that weirdness. In this late work though, weirdness is never trivial, and austerity never confining. If the sublime foreshadows our mortality, this music might communicate the austerity of death – Fauré’s as it approached him, but also the apprehension of our own. We find a kinship with the composer finally, in the form of a question that he tossed off into the future, to us.

I have composed four pieces Après Fauré to accompany Fauré’s music here, to share the way I have engaged with Fauré’s question, with you the listener. This format is similar to my After Bach project. The connections are less overt, but Fauré’s harmonic imprint is on all four. There is also a textural influence, in terms of how he presented his musical material pianistically – he exploited the instrument’s sonority masterfully, as an expressive means. So, for example, in my first “Prelude”, melody is welded to a continuous arppegiation, both part of it and hovering above it; in my “Nocturne”, it is possible to hear the harkening chordal approach in the opening of Fauré’s No. 12.

The record ends with a reduction of an excerpt from the Adagio movement of the aforementioned Piano Quartet in G Minor. This music is quintessential Fauré, in its ability to draw the listener into what feels like a waking dream, a consoling reverie that only gains expressive power in its delicate ephemerality. It is mysterious and bewitching

Brad Mehldau